Journey from Scotland

Departing Kintail

|

| Kintail to Isleornsay overland and sea routes John Thomson's Atlas of Scotland, 1832 detail from Northern Part of Ross and Cromarty Shires. Southern Part. National Library of Scotland |

More likely the MacRaes took the faster, more direct route by boat from Loch Duich, past the ruins of Eilean Donan castle, into Loch Alsh, then heading south west into Kyle Rhea towards the Sound of Sleat until reaching Isleornsay. Travelling with the tide, this can be done in a matter of hours.

|

| William Daniel, Loch Duich, Rosshire, 1818, from Ayton & Daniell's Voyage round Great Britain, Vol. 4, plate 100, Aquatint, 162 x 241 mm |

As young Mary was about nine, little John was only six months old and little Hellen, the daughter of Alexander McRae and Ann Beaton, also an infant, whichever way the journey would have been tiresome.

It also seems likely that the two MacRae families travelled together with the other Highland families, such as the MacIntoshes and McLennans, who were also departing on the William Nicol.

Background and Preparations

The voyage was made possible by the vision of two like-minded clergyman. One a distinguished minister of the Scottish Church, Rev. Norman MacLeod, also known in Gaelic as Caraid nan Gàidheal, or friend of the Gael, for his contribution to the welfare and education of the Highlanders. The other, Rev. John Dunmore Lang, a native of Scotland, the first Presbyterian minister in the Colony of New South Wales and ardent advocate and promoter of the immigration of free settlers to the Colony of New South Wales; especially of families, skilled tradesmen and much needed experienced agricultural workers.The Rev. Lang was in attendance when an impassioned plea for help for the Highlanders was given by Rev. MacLeod at the residence of the Lord Mayor of London in March 1837. Rev. Lang had already been instrumental in bringing free settlers from Scotland to Australia. This voyage was the first from Scotland assisted by the British Government using funds raised from the sale of Crown land in Australia to cover the costs. It was to benefit all concerned as Australia gained much need skilled labour, especially skilled tradesmen and experience agricultural workers, and the plight of the famine-stricken Highlanders was alleviated.

|

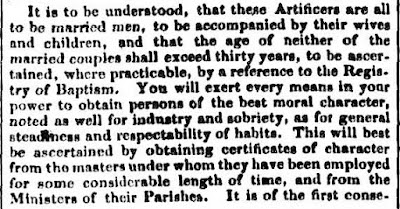

| extract from, IMMIGRATION. Letter of Instructions from the Colonial Secretary, to David Boyter, Esquire, Surgeon, R. N., 10th February, 1836 |

Although these instructions were given sometime prior to the departure of the William Nicol and there had been a number of follow-up letters discussing the selection criteria, at the time the William Nicol sailed, the aged limit was still 30 years. Dr. Boyter, however, found it impossible to adhere to the instructions regarding age, and instead made arrangements, whereby in such cases, accommodation was provided on board but they were to pay the Master of the Ship for their rations. Shortly after this the aged limit was increased to 35 years.

| Passenger List for the William Nicol arrived Sydney 27 October 1837 © NSW State Archives and Records |

It is likely that both Farquhar and Alexander "reduced" their ages slightly in order to secure a passage on the William Nicol. If the age on Farquhar's headstone is correct then he died aged 96 in 1892, making him aged 41 at the time of his journey to Australia. More likely, as his Death Certificate states that he died aged 92, he was probably aged 36 not aged 32 as recorded on the ship's passenger list.

Similarly, with regards to Alexander's age. In a letter written in 1876, found by one of Farquhar's descendants on a trip to Scotland in a library or archive in Glasgow, Alexander writes that he is aged 73. So this makes him aged 34 in 1837, not aged 30 as stated. It could be deduced from this that Farquhar and Alexander were keen to emigrate and start a new life in Australia.

Noticeably absent from the passenger list are the names of their wives and children although the number of children was recorded.

|

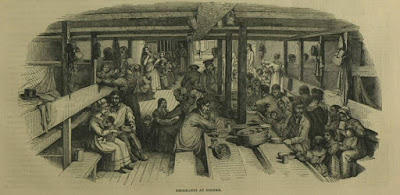

| Embarkation of Highlanders for Australia |

Embarkation

Isleornsay was a natural harbour sheltered by the Isle of Ornsay and had been a port of departure for many Scots, mainly for North America, since that 1790s. There was a an Inn and a large shop from which goods were traded with Europe and North America. It was also at that time an important port for the west coast Herring trade.So no doubt the locals were well prepared for the sudden influx of 300 plus passengers intending to board the William Nicol. It took 3 days for all passengers to be cleared and the ship made ready to sail.

The ship, with Captain John McAlpine in command, set sail amid much fanfare and celebration. The John O'Groat's Journal reported that on the evening prior to departure "dancing commenced on board to the enlivening notes of the bagpipe and was kept up till a late hour" and next morning as the ship passed Armadale Castle, the Seat of the MacDonalds of Sleat, there was a twelve gun salute which the ship returned, cheered on by the passengers.

From the Medical journal of Dr. George Roberts, the ships Surgeon, it is known that there was 323 passengers and that the ship was fitted out to accommodate 222 adults. An adult was allocated 18 inches (46 cm) of deck space, equal to the space allowed on convict ships. "The children were birthed as near as possible to the following ratio, viz, 2 above 7 years to an adult, and 3 under that age to an adult". There were "males adults 69, females adults 75, children above 7 years, 72 and children under that age 107" and a crew of 24.

The John O'Groat's Journal informs us that including the MacRaes, 43 passengers came from Ross‑shire and that "judging from appearances, there is likely to be a considerable addition to the passengers before the ship reaches her destination". Sadly two of the pregnant women mentioned did not survive the voyage, dying at sea as a result of childbirth. One of whom was Flora, the wife of Alex MacKenzie, who died after giving birth to triplets on 7 October 1837.

On board the William Nicol

When the MacRaes boarded the William Nicol it would have been with thoughts of never returning to their home land; never to see their families and friends, never to see the Lochs and the snow covered Sgùrr. Sentiments much as those expressed in the ballad "I canna leave my Heiland Hame" |

| Artist unknown William Nicol H & M Reed and Clyde Maritime Research Trust |

So mixed with feelings of loss and separation would also have been feelings of relief, excitement, hope, adventure and dreams of a better life. Little did the MacRaes know at the time that those left behind in Scotland were to experience even greater hardship with more evictions and the Great Famine of 1846.

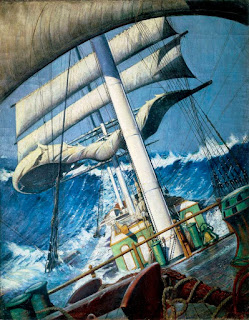

There were to be many challenges ahead. First they had to endure 113 days at sea in cramped and unhygienic conditions, dimly lit by the light from smokey, smelly oil lamps, travelling approximately 13,000 nautical miles including through the notorious Roaring Forties.

The first part of the journey, until nearing the equator, was a time of adjustment and possibly bad weather. Dr. Roberts' Journal noted that once at sea "they suffered in general from sea sickness which rendered many of them quite helpless for a time. Surprisingly, he also wrote that “they felt little inconvenience from the crowded conditions”. Then he added, “but on approaching the tropics and the temperature increasing, they having inhabited open country and accustomed to the least constraint, their suffering became distressing". With the rise in temperature also came exotic tropical fish visible in the waters along side the ship, and the opportunity to leave the crowded accommodation to spend more time on deck.

Their accommodation on ship was not unlike these pictures from the Illustrated London News except that an additional row of berths was erected up the middle of the ship further reducing the circulation of air and compounding the congestion.

| Illustrations of life on board (steerage class) from Illustrated London News, 1844, 1849 & 1851 |

There were very limited bathing and washing facilities on board so it is not surprising that Dr Roberts also records "arising apparently from their crowded condition, the number of young children and the uncleanly habits of the people in general, produced between decks a loaded and impure atmosphere, with mephitic effusion, which proved highly deleterious in every respect to the health of the children". As the following excerpt from Dr Roberts journal explains every measure was taken to maintain hygiene, air of bedding, and scraping and fumigation of desks .....

|

| extract from Dr. Roberts' journal |

The only chance to wash clothes came after a storm, when water could be collected from the sails and awnings. On most voyages passengers were expected to bring with them enough changes of clothing for the journey. Many assisted migrants could not afford to do so.

They were not long on board when Allan MacDonald's wife aged 32, was recorded on 6 July as having the first case of diarrhoea, and the first death was recorded on 11 July with the death of Donald Cameron's child, aged ten months, from fever. There were 17 deaths from a total of 146 cases of illness recorded. All but two of these deaths occurred before they reached the Cape of Good Hope and 15 were infants or children under the age of five. Diarrhoea was the most common complaint of which there were 37 cases, including the infant children of Farquhar and Alexander, John and Helen, who were both treated for diarrhoea on the 15 July which lasted four to five days. Imagine going on a cruise today and 17 people on the cruise ship died. Even on the average size ocean liner with 3,000 passengers, with a good percentage of elderly passengers, this would be extraordinary, apart from serious incidents such as a fire on board or a collision.

|

| Cape of Good Hope - The Emigrant Ship William Nicol |

Table Bay was the first and only port of call for the journey. The Parbury's Oriental Herald and Colonial Intelligencer reported that there "was a great want of water-closets, and other necessities of cleanliness. Many of the children had died, and all the women and children were sickly, from injudicious selection of food." The passengers were not permitted to disembark at Table Bay and although the lack of interpretor is mentioned, others record that a Mrs. MacDonald, who was a midwife, assisted the ship's surgeon as a translator.

Reports of the harsh conditions led to money being raised by the locals for fresh food and additional clothing for the women. Dr. Boyter was later to refute most of these claims. However, one immediate result of the reports from Cape of Good Hope, was that on subsequent ships there was a reduction in the number of passengers together with an increase in deck space per person, to diminish the crowding and improve hygiene. (Here is a copy of the original correspondence regarding the conditions on the William Nicol kindly provided by Kerry Budgen.)

The ship stayed in Table Bay only a few days, embarking on 15 September 1837 sailing into the Roaring Forties and passing what is now known as the Shipwreck coast, the limestone coast of South Australia and the south west coast of Victoria. They had 41 more days at sea before they were to reach Sydney.

|

| Wenceslaus Hollar and John Overton, A Flute in the Trough of a Sea and a Ship Scudding, 1665, etching Mount: 123 mm x 271 mm © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London |

|

| John Everett, The Deck of the Barque 'Endymion' in a Heavy Sea, oil on paper, late 19th century - mid 20th century, © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London |

Depending on the route taken, the first sighting of land and sign that they were nearly at their journey's end, may have been when passing through Bass Strait. By comparison, today a cruise from the United Kingdom to Australia with stopovers takes 50 days and a world cruise including stopovers and covering roughly twice the distance takes about the same time that the William Nicol took. Although the journey was slow by today's standards, the William Nicol did the trip in less than half the time taken by the First Fleet, 50 years earlier which took 252 days.

From artists' impressions around the time, is gained a sense of what it was like sailing through Sydney Heads into Port Jackson. After 113 days at sea in crowded conditions and 17 deaths amongst their companions, there must have been a great sense of achievement having finally reached their destination, an eagerness to have earth under their feet once again, combined with the wonder at the beauty of Sydney Harbour.

|

| Artist Unknown Sydney Heads from South Head, 1843, National Library of Australia |

|

| Augustus Earle, Sydney Heads, 1825, Earle's Lithography, Sydney, N.S.W National Library of Australia |

|

| Richard Read, View of Sydney Cove taken from the North shore, Port Jackson, N.S.Wales, 1820, National Library of Australia |

|

| Walter G. Mason, The Government Jetty,Port Jackson, published by J. R. Clarke, 1857 National Library of Australia |

They sailed into Sydney Harbour on the morning of 27 October 1837, with passengers now, according to The Sydney Monitor, "311 Emigrants, comprising 69 males and 73 females— adults ; and 169 children." Five of these children having been born at sea.

|

| Scotch Emigrants |

The Sydney Herald reported a that "great concourse of persons assembled, and at twelve o'clock precisely, the sheriff, accompanied by the Governor and staff &c., came into the verandah" at Government House and the proclamation was read. "When the sheriff had concluded three cheers were given by the assembled crowd". After which "the standards were then hoisted to the mast-heads and a Royal salute fired from the guns at the Dawes' Point". This was followed by a large procession, some dressed in mourning, consisting of the band and a division of the 50th Regiment, a number of inhabitants of Sydney, a number of senior officials, Judges, Clergy and members of Parliament, including the Attorney General, and detachments of the 4th, 50th and 80th regiments.

The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser added that the "vessels in the harbour hoisted their numerous flags, and as seen from the front of Government House had a most beautiful appearance". Perhaps the William Nicol was among the ships referred to. Having left Scotland after the death of King William, the passengers on the William Nicol may have already known this news even so the excitement and celebratory mood on the streets of Sydney would have been a most welcoming sight.

After having survived on a diet of largely salted meat and bread while at sea, thoughts of fresh meat, milk and vegetables must have been at the forefront of their minds and whatever food was served up at the Immigration Barracks must have tasted delicious. Given the distress and hardship of the journey, it is not surprising that neither Farquhar, Barbara, Alexander nor Ann ever took the return journey back to Scotland.

More information on the journey can be found in "The Voyage of the William Nicol 1837" (Sick Book for 4 July to 16 July appended), the undated and unpublished research paper of E. Finn, a descendant of Farquhar MacRae, kindly provided by Patrick MacRae, Helensburgh, with appended Sick Book courtesy of Bernadette MacRae, Gold Coast.

Many thanks to Maggie Mcdonald, Secretary, Eachdraidh Shlèite, Sleat Local History Society for background information on Kintail and Isleornsay

|

| C. Hamilton, Port Jackson from the Lighthouse, 1850, 1 watercolour ; 16.5 x 74.50 cm, National Library of Australia |

Mentioned on this page (in the order mentioned)

● 1832, Northern Part of Ross and Cromarty Shires. Southern Part. John Thomson's Atlas of Scotland, National Library of Scotland viewed 27 Oct 2017 http://maps.nls.uk/view/74400155

● 1837 "IMMIGRATION. Letter of Instructions from the Colonial Secretary, to David Boyter, Esquire, Surgeon, R. N., 10th February, 1836", The Australian (Sydney, NSW : 1824 - 1848), 6 June, p. 2. , viewed 04 Nov 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article36856920

● 1837 'Distress In Scotland'. The Observer (1791- 1900), 12 March, viewed 28 Ocot 2017, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.sl.nsw.gov.au/docview/474002820?accountid=13902 [State Library of NSW Library card or similar required to view online]

● Passenger List for the William Nicol arrived Sydney 27 October 1837 page 1, NSW State Archives: NRS5313 Persons on government ships, Aug 1837-Feb 1840, William Nicol 27 Oct 1837 [4/4780], Reel 2654, viewed 08 Sep 2015, https://www.records.nsw.gov.au/archives/collections-and-research/guides-and-indexes/assisted-immigrants-digital-shipping-lists

● 1837 "Scotland. Embarkation of Highlanders for Australia", John O'Groat Journal, 21 July, p. 2. British Library Newspapers, viewed 25 Oct 2017, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5NwuY9 [State Library of NSW Library card or similar required to view online]

● 1844 "Emigration to Sydney." Illustrated London News, 13 April, p. 229+. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003, viewed 08 Nov 2107, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5TZTR7 [State Library of NSW Library card or similar required to view online]

● 1849 "Emigration.—A Voyage to Australia." Illustrated London News, 20 January, p. 39+. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003, viewed 08 Nov 2107, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5TZU47 [State Library of NSW Library card or similar required to view online]

● 1851 "The Depopulation of Ireland." Illustrated London News, 10 May, p. 386+. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003, viewed 08 Nov 2107, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5TZdB3 [State Library of NSW Library card or similar required to view online]

● Roberts, George, R.N. Surgeon and Superintendent, 1837, "Medical and surgical journal of the William Nicol emigrant ship for 3 July to 28 October 1837", viewed 28 Oct 2017, The National Archives of United Kingdom, http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/browse/r/h/C4107037

● 1838 'Emigration from the Western Islands of Scotland to Australia.', The Sydney Monitor and Commercial Advertiser (NSW : 1838 - 1841), 7 November, p. 2. (MORNING : SUPPLEMENT TO THE SYDNEY MONITOR AND COMMERCIAL ADVERTISER.), viewed 05 Nov 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32161813

● "I canna leave my Hieland Hame", Word on the Street, National Library of Scotland, viewed 23 Oct 2017, http://digital.nls.uk/broadsides/broadside.cfm/id/20854

● "William Nicol", painting, artist and date unknown, The History of Ship Building in Scotland, Clyde Maritime Research Trust, viewed 21 Sep 2017, http://www.clydeships.co.uk/view.php?ref=18300

● 1837, "Cape of Good Hope. Shipping" The Asiatic Journal (London, England), [Friday], 1 December, pg. 282, Issue 96, Empire, 19th Century UK Periodicals, Gale Document Number: CC1903300258, viewed 28 Oct 2017, http://find.galegroup.com.ezproxy.sl.nsw.gov.au/dvnw/infomark.do?&source=gale&prodId=DVNW&userGroupName=slnsw_public&tabID=T003&docPage=article&docId=CC1903300258&type=multipage&contentSet=LTO&version=1.0 [State Library of NSW Library card or similar required to view online]

● 1838, "Cape of Good Hope, The Emigrant Ship William Nicol", Nicol, Parburys Oriental Herald and Colonial Intelligencer, January To June, Parbury & Co., p.37., Internet Archive, viewed 28 Oct 2017, archive.org/download/in.ernet.dli.2015.31054/2015.31054.Parburys-Oriental-Heraldjanuary-To-June.pdf

● 1838, "Shipping", The Asiatic Journal (London, England), 1 January, pg. 47, Issue 97, Empire, 19th Century UK Periodicals, Gale Document Number: CC1903300414, viewed 28 Oct 2017, http://find.galegroup.com.ezproxy.sl.nsw.gov.au/dvnw/infomark.do?&source=gale&prodId=DVNW&userGroupName=slnsw_public&tabID=T003&docPage=article&docId=CC1903300414&type=multipage&contentSet=LTO&version=1.0 [State Library of NSW Library card or similar required to view online]

● 1837 'Scotch Emigrants.', The Sydney Monitor (NSW : 1828 - 1838), 27 October, p. 3. (EVENING), viewed 11 Nov 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32157839

● 1837 'PROCLAMATION OF THE QUEEN.', The Sydney Herald (NSW : 1831 - 1842), 30 October, p. 2. , viewed 11 Nov 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article28653234

● 1837 'Price Current of Colonial Wool.', The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 - 1842), 28 October, p. 3. , viewed 27 Nov 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2213668

Further reading

● 1837 'SHIP NEWS.', The Sydney Herald (NSW : 1831 - 1842), 30 October, p. 2. , viewed 11 Nov 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article28653243

● 1837 'THE LATE EMIGRATION SYSTEM.', The Sydney Herald (NSW : 1831 - 1842), 14 August, p. 2. , viewed 07 Nov 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12857210

● 1838, Emigration To Australia" The Aberdeen Journal (Aberdeen, Scotland), 19 September, Issue 4731 viewed 28 Oct 2017, British Library Newspapers, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5Q2yd7 [State Library of NSW Library card or similar required to view online]

● 1838 'Ship News.', The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 - 1842), 21 June, p. 2. , viewed 10 Nov 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2550195

● 1853 Samuel Mossman and Thomas Banister, Australia Visited and Revisited, A Narrative of Recent Travels and Old Experiences in Victoria and New South Wales, A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook, Published by Addey and Co.,London, p. viewed 10 Nov 2017, http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks16/1600061h.html#ch-01

● 1888 'STATUE OF THE REV.J.D.LANG.', South Australian Weekly Chronicle (Adelaide, SA : 1881 - 1889), 15 December, p. 11. , viewed 25 Oct 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article94766679

● D. W. A. Baker, published first in hardcopy 1967," Lang, John Dunmore (1799–1878)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, viewed 24 Oct 2017, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/lang-john-dunmore-2326/text2953

● Eachdraidh Shlèite Sleat Local History Society, "Emigration", viewed 24 Oct 2017, http://www.sleatlocalhistorysociety.org.uk/index.php/topic/48

● International Shipping Facts and Figures – Information Resources on Trade, Safety, Security, Environment, International Maritime Organistion (IMO), viewed 1 Nov 2017, http://www.imo.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/ShipsAndShippingFactsAndFigures/TheRoleandImportanceofInternationalShipping/Documents/International%20Shipping%20-%20Facts%20and%20Figures.pdf

● Katherine Foxhall, 'Fever, Immigration and Quarantine in New South Wales, 1837–1840', Social History of Medicine Vol. 24, Issue 3, pp. 624–642, viewed 21 July 2019, https://academic.oup.com/shm/article/24/3/624/1641803.

● "Scottish History", Electrics Scotland website, viewed Oct 2017, http://www.electricscotland.com/history/index.htm

● Southward Bound, Life Onboard, Online Programs, South Australian Maritime Museum Education Service, viewed 08 Nov 2017, http://education.maritime.history.sa.gov.au/docs/southwardbound.pdf

● "The MacRaes", viewed 13 Nov 2017, http://www.melodiesplus.com/Mary/macraeclearances.htm

● 1832, Northern Part of Ross and Cromarty Shires. Southern Part. John Thomson's Atlas of Scotland, National Library of Scotland viewed 27 Oct 2017 http://maps.nls.uk/view/74400155

● 1837 "IMMIGRATION. Letter of Instructions from the Colonial Secretary, to David Boyter, Esquire, Surgeon, R. N., 10th February, 1836", The Australian (Sydney, NSW : 1824 - 1848), 6 June, p. 2. , viewed 04 Nov 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article36856920

● 1837 'Distress In Scotland'. The Observer (1791- 1900), 12 March, viewed 28 Ocot 2017, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.sl.nsw.gov.au/docview/474002820?accountid=13902 [State Library of NSW Library card or similar required to view online]

● Passenger List for the William Nicol arrived Sydney 27 October 1837 page 1, NSW State Archives: NRS5313 Persons on government ships, Aug 1837-Feb 1840, William Nicol 27 Oct 1837 [4/4780], Reel 2654, viewed 08 Sep 2015, https://www.records.nsw.gov.au/archives/collections-and-research/guides-and-indexes/assisted-immigrants-digital-shipping-lists

● 1837 "Scotland. Embarkation of Highlanders for Australia", John O'Groat Journal, 21 July, p. 2. British Library Newspapers, viewed 25 Oct 2017, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5NwuY9 [State Library of NSW Library card or similar required to view online]

● 1844 "Emigration to Sydney." Illustrated London News, 13 April, p. 229+. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003, viewed 08 Nov 2107, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5TZTR7 [State Library of NSW Library card or similar required to view online]

● 1849 "Emigration.—A Voyage to Australia." Illustrated London News, 20 January, p. 39+. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003, viewed 08 Nov 2107, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5TZU47 [State Library of NSW Library card or similar required to view online]

● 1851 "The Depopulation of Ireland." Illustrated London News, 10 May, p. 386+. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003, viewed 08 Nov 2107, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5TZdB3 [State Library of NSW Library card or similar required to view online]

● Roberts, George, R.N. Surgeon and Superintendent, 1837, "Medical and surgical journal of the William Nicol emigrant ship for 3 July to 28 October 1837", viewed 28 Oct 2017, The National Archives of United Kingdom, http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/browse/r/h/C4107037

● 1838 'Emigration from the Western Islands of Scotland to Australia.', The Sydney Monitor and Commercial Advertiser (NSW : 1838 - 1841), 7 November, p. 2. (MORNING : SUPPLEMENT TO THE SYDNEY MONITOR AND COMMERCIAL ADVERTISER.), viewed 05 Nov 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32161813

● "I canna leave my Hieland Hame", Word on the Street, National Library of Scotland, viewed 23 Oct 2017, http://digital.nls.uk/broadsides/broadside.cfm/id/20854

● "William Nicol", painting, artist and date unknown, The History of Ship Building in Scotland, Clyde Maritime Research Trust, viewed 21 Sep 2017, http://www.clydeships.co.uk/view.php?ref=18300

● 1837, "Cape of Good Hope. Shipping" The Asiatic Journal (London, England), [Friday], 1 December, pg. 282, Issue 96, Empire, 19th Century UK Periodicals, Gale Document Number: CC1903300258, viewed 28 Oct 2017, http://find.galegroup.com.ezproxy.sl.nsw.gov.au/dvnw/infomark.do?&source=gale&prodId=DVNW&userGroupName=slnsw_public&tabID=T003&docPage=article&docId=CC1903300258&type=multipage&contentSet=LTO&version=1.0 [State Library of NSW Library card or similar required to view online]

● 1838, "Cape of Good Hope, The Emigrant Ship William Nicol", Nicol, Parburys Oriental Herald and Colonial Intelligencer, January To June, Parbury & Co., p.37., Internet Archive, viewed 28 Oct 2017, archive.org/download/in.ernet.dli.2015.31054/2015.31054.Parburys-Oriental-Heraldjanuary-To-June.pdf

● 1838, "Shipping", The Asiatic Journal (London, England), 1 January, pg. 47, Issue 97, Empire, 19th Century UK Periodicals, Gale Document Number: CC1903300414, viewed 28 Oct 2017, http://find.galegroup.com.ezproxy.sl.nsw.gov.au/dvnw/infomark.do?&source=gale&prodId=DVNW&userGroupName=slnsw_public&tabID=T003&docPage=article&docId=CC1903300414&type=multipage&contentSet=LTO&version=1.0 [State Library of NSW Library card or similar required to view online]

● 1837 'Scotch Emigrants.', The Sydney Monitor (NSW : 1828 - 1838), 27 October, p. 3. (EVENING), viewed 11 Nov 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32157839

● 1837 'PROCLAMATION OF THE QUEEN.', The Sydney Herald (NSW : 1831 - 1842), 30 October, p. 2. , viewed 11 Nov 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article28653234

● 1837 'Price Current of Colonial Wool.', The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 - 1842), 28 October, p. 3. , viewed 27 Nov 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2213668

Further reading

● 1837 'SHIP NEWS.', The Sydney Herald (NSW : 1831 - 1842), 30 October, p. 2. , viewed 11 Nov 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article28653243

● 1837 'THE LATE EMIGRATION SYSTEM.', The Sydney Herald (NSW : 1831 - 1842), 14 August, p. 2. , viewed 07 Nov 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12857210

● 1838, Emigration To Australia" The Aberdeen Journal (Aberdeen, Scotland), 19 September, Issue 4731 viewed 28 Oct 2017, British Library Newspapers, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5Q2yd7 [State Library of NSW Library card or similar required to view online]

● 1838 'Ship News.', The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 - 1842), 21 June, p. 2. , viewed 10 Nov 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2550195

● 1853 Samuel Mossman and Thomas Banister, Australia Visited and Revisited, A Narrative of Recent Travels and Old Experiences in Victoria and New South Wales, A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook, Published by Addey and Co.,London, p. viewed 10 Nov 2017, http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks16/1600061h.html#ch-01

● 1888 'STATUE OF THE REV.J.D.LANG.', South Australian Weekly Chronicle (Adelaide, SA : 1881 - 1889), 15 December, p. 11. , viewed 25 Oct 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article94766679

● D. W. A. Baker, published first in hardcopy 1967," Lang, John Dunmore (1799–1878)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, viewed 24 Oct 2017, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/lang-john-dunmore-2326/text2953

● Eachdraidh Shlèite Sleat Local History Society, "Emigration", viewed 24 Oct 2017, http://www.sleatlocalhistorysociety.org.uk/index.php/topic/48

● International Shipping Facts and Figures – Information Resources on Trade, Safety, Security, Environment, International Maritime Organistion (IMO), viewed 1 Nov 2017, http://www.imo.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/ShipsAndShippingFactsAndFigures/TheRoleandImportanceofInternationalShipping/Documents/International%20Shipping%20-%20Facts%20and%20Figures.pdf

● Katherine Foxhall, 'Fever, Immigration and Quarantine in New South Wales, 1837–1840', Social History of Medicine Vol. 24, Issue 3, pp. 624–642, viewed 21 July 2019, https://academic.oup.com/shm/article/24/3/624/1641803.

● "Scottish History", Electrics Scotland website, viewed Oct 2017, http://www.electricscotland.com/history/index.htm

● Southward Bound, Life Onboard, Online Programs, South Australian Maritime Museum Education Service, viewed 08 Nov 2017, http://education.maritime.history.sa.gov.au/docs/southwardbound.pdf

● "The MacRaes", viewed 13 Nov 2017, http://www.melodiesplus.com/Mary/macraeclearances.htm